The principle of the criminal justice system is simplicity itself: if you break the law, you’ll be punished, and if the law you’ve broken is big enough and bad enough, the punishment, in all probability, will be imprisonment. In practice, alas, implementing the penal code has proven… problematic. Corruption is commonplace, wrongful convictions are rife, and the sheer number of people incarcerated each year is distressing at best. In the US alone, there are more than two million individuals under lock and key as we speak, and that number may even have increased by 2048, when the bulk of One Way takes place.

Compounding this particular problem is the irrefutable fact that every prisoner has rights. Not necessarily to liberty, but to life, in that they can still count on meals and a place to sleep at least. That’s neither offensive nor expensive in itself, but multiplied however many million-fold, the prospect of three hots and a cot can start to cost an awful lot. To square that essential outlay away, standard procedure today is to put prisoners to work, and it’s to that practice real-life rocket scientist S. J. Morden appends his text’s premise. What if, he wonders in One Way, we sent some of them—the lifers and the like that have nothing left to lose—to Mars, to make a base?

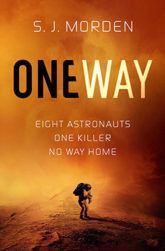

Buy the Book

One Way

One Way’s principal perspective is Franklin Kittridge’s, and he’s a killer. At the end of his tempestuous tether and fearing for his family’s future, he shot his beloved boy’s drug dealer dead, for which crime he was condemned to no less than ninety years. He’s already in his fifties when the book begins, and his wife and child have cut all ties to him, so when he’s approached by the Powers That Be at Panopticon—the ominously-named owners of several private prisons—with the offer outlined above, he has a great deal to gain, and no real reason to refuse.

Now Frank won’t be free on Mars, if he even makes it there—there’s an intensive training regimen to start and finish first—but he’ll have a lot more liberty on the Red Planet than he does in the penitentiary in which he’s currently confined. His job, as a former engineer, will be to help build a habitable facility for the astronauts NASA aim to send along later to live in. He won’t have to do it himself, either: six other prisoners in similar situations to his, each with their own area of expertise, have been roped in on this ridiculousness.

So far, so silly in synopsis, but Morden does a remarkably good job of rationalising his text’s apparently preposterous premise. We’re privy, for reasons that only become clear come One Way’s brutal conclusion, to a selection of interstitial emails and memos from the company that hatched this dastardly plan, and the reasoning revealed therein is sure to prove painfully familiar to anyone who’s ever done something ambitious on a budget.

Speaking of: saving money is pretty much Panopticon’s parent company’s modus operandi, meaning that when Frank and his felonious associates finally do make it to Mars, they have almost none of the things they need. They were always going to have to build a base from the bottom up, but a lot of their essential supplies have been lost, or not sent at all in some cases, making it a mad scramble to (deep breath) generate power to make air in order to produce water to feed to life-sustaining seeds—and so on.

What with its focus on survival and hard science, this section of One Way—which is to say most of the middle act—is not a little reminiscent of Andy Weir’s work. Thankfully, Morden makes it his own by insinuating a murder mystery into the midst of his prisoners’ many problem-solving sessions. People keep dying, you see, and although Frank assumes the deaths are accidental initially—as indeed would we if One Way wasn’t being sold as a thriller about a killer—eventually the evidence starts to suggest something more sinister. Could there be a murderer amongst the only men and women on Mars?

Well, yes. There are several—up to and including Frank, in fact—and that’s part of what makes Morden’s novel so neat. A rogue’s gallery of likely suspects make it damnably difficult to guess who’s gone rogue, and it’s a credit to the author that the solution, when it’s revealed, is not just surprising—it’s also surprisingly satisfying. In the interim, the sense of tension that One Way has in abundance from the second its convicts set foot on the Red Planet is brilliantly bolstered by the suspicions that settle on successive survivors. In a move right out of Agatha Christie’s rulebook—And Then There Were None, anyone?—the longer a character lives, the more guilty he or she seems.

One Way is substantially less successful, sadly, when it comes to its cast. Frank, for his part, is fine: a cold-blooded killer, to be sure, but one with an emotional motive that speaks to how much he loves his son. As such, he’s somewhat sympathetic, though none of the others, whose criminal histories are for the most part treated as mysteries, are nearly as appealing. They live for a little while, lacking the critical context and relative complexity Morden furnishes Frank with, then they die, and absent any real resonance, their deaths are practically plot points.

This dearth of depth is doubly disappointing because One Way is tremendously successful in every other respect. Burdened with bland characters it may be, yet it remains very entertaining, and in shifting gears so frequently—from prison-focused fiction to hectic whodunit via some skilful survival sci-fi—it’s guaranteed to keep its readers on the edge of their seats till its desperate denouement. I mean, sure, One Way isn’t even the most serious story you’ll read this week, despite its provocative premise. If that’s what you’re after, know that this is not the book for you. Morden is more interested in imagining what might happen if Orange is the New Black was to meet The Martian, and for my part, once I’d put aside my personal politics, I was perfectly happy with that.

One Way is available from Orbit in the US and from Gollancz in the UK.

Niall Alexander is an extra-curricular English teacher who reads and writes about all things weird and wonderful for The Speculative Scotsman, Strange Horizons, and Tor.com. He lives with about a bazillion books, his better half and a certain sleekit wee beastie in the central belt of bonnie Scotland.